Poker

Poker

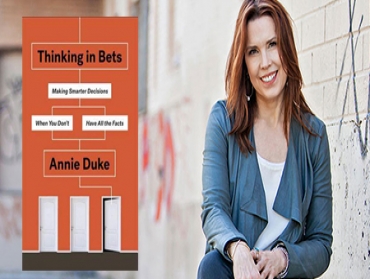

A review of Annie Duke’s latest book

American professional poker player and author Annie Duke is a well known figure in the world of poker. While she has not been as active in recent years at the felts, till not too long ago she was the leading money winner among women in World Series of Poker. She even holds a WSOP gold bracelet which she won in the 2004 edition.

Duke has been writing poker and related books for the past decade. Her book “Decide to Play Great Poker”, a strategy book for no-limit hold’em, was published in June 2011 followed by a second book, “The Middle Zone”, which focused on strategy for difficult hands. In addition to her instructional books, Duke released an instructional DVD series including “Annie Duke’s Advanced Texas Hold’em Secrets: How to Beat the Big Boys” and in 2005 she launched a range of poker products with ESPN.

Her latest book “Thinking in bets: Making smarter decisions when you don’t have all the facts” is not a book about poker strategy or gambling, though. “It is about things poker taught me about learning and decision-making,” she explains. It contains solutions for anyone who wants to be a better decision-maker.

This book is important because life is like poker, not chess. In chess you can simply work backwards from the quality of the outcome to determine the quality of the decisions that were made. In chess, there must be a right procedure for any position in the game, because the game of chess does not involve hidden information, and luck plays virtually no part. The pieces are all there for both players to see, and they can’t randomly appear or disappear from the board or get moved by chance.

All the complexity of chess does not make it a good model for decision-making in life. Our lives and most of our decisions involve hidden information, and luck plays a far greater role. Poker is far more instructive. Most poker hands end in with incomplete information: one player bets, no one calls the bet, and the bettor is awarded the pot. No player is required to reveal their hidden cards, and so the players are left guessing why they won or lost the hand.

Every hand in poker involves making at least one decision, and some hands involve as many as 20 decisions. In a single session, a poker player makes hundreds of decisions, all of which are taking place at great speed. In a high-stakes game, each decision can be worth more than an average three-bedroom house, made more quickly than the decision of what to order in a restaurant.

Like poker, our lives are the result of two things: the influence of skill and the influence of luck, and often a combination of the two. In life it is difficult to tell why anything happened the way it did. And every decision we make always involves some risk: money, time, health, happiness, etc. A bet is a decision about an uncertain future. ‘Thinking in Bets’ the title of the book “makes it possible for me to find learning opportunities in uncertain environments,” Duke explains. Treating decisions as bets is a technique to avoid common decision traps and to keep emotions out of the process as far as is possible. It helps toward objectivity, accuracy, and open-mindedness.

A common decision trap is to confuse decisions and results. A good-quality decision can have a bad result, just as a bad decision can have good result. Poker players call this “resulting”. It is a consequence of drawing an overly tight relationship between results and decision quality, ignoring the role that luck and skill can play in any decision. Consider a hire that went wrong. After a long search and a rigorous selection process for experience and skill, you brought a senior person into the company. With the collapse of your closest competitor, the market dynamics changed drastically, requiring abilities beyond the capacity and experience of your new executive. The hiring decision was a good one, based on all you knew at the time. The result was a bad one.

Related to this trap is the its companion, the hindsight bias. With hindsight it was a bad decision, but with what you knew at the time, it may have been a good decision. The hindsight bias is the tendency, after the outcome is known, to see the outcome as having been inevitable. Conversely, when we make decisions for the future, we encounter different problems. First, we get only one try at any given decision – no more. This creates great pressure to be certain before acting, and so we overlook the influence of hidden information and luck. Most of us don’t want to be the person who learns: we want to be the person who knows. Admitting that we don’t know has an undeservedly bad reputation.

Since a good decision is not one that necessarily has a great outcome, rather one that is the result of a good process, the decision process must include an attempt to accurately represent our knowledge at the time. Our knowledge must, almost always, include some variation of “I’m not sure”. What good poker players and good decision-makers have in common is their comfort with the world being an uncertain and unpredictable place. Imagine your doctor using a scale with only two measures: 15 kilos and 150 kilos with nothing in between. You would either be severely underweight or severely overweight. A ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ decision is equally flawed. For most of our decisions, there will be a lot of space between an unequivocal ‘right’ decision and a ‘wrong’ one.

Acknowledging uncertainty is the first step in measuring and narrowing it. We are inclined to assume that if we don’t appear 100% confident, others will value our opinions less. In fact, others might be reluctant to offer new and relevant information only because we seem so certain. Alternately, if others are equally certain they are correct, they might be afraid of making us feel bad or judged and so not offer their view.

By evaluating our level of confidence by saying, “I’m 80% sure” we open the door for others to tell us what they know. A bet is a monetary commitment to a level of certainty, and if we thought of each decision as a bet, (which it always is,) we are forced to calibrate our level confidence. “When a friend says, ‘Wanna bet?’, suddenly, you’re not so sure,” Duke notes. That challenge forces you to pause and perhaps back down from your assertion and question the belief that you just declared with confidence. Thinking in bets in this very literal sense is just one of the very useful decision-making tools Duke introduces. Poker has a lot to teach about the decision-making that we engage in daily.

Top 15 Poker Rooms

-

WPT Global

Grab your welcome offer

Offer: 100% of your deposit back up to $3,000 Register -

PokerDangal

Sign up with code GUTSHOT1

Offer: Get 100% GST discount on deposits Register -

Natural8 India

Sign-up with Gutshot

Offer: Get extra 28% on all deposits Register -

Spartan Poker

Sign-up with referral code AFFGSMAG

Offer: FTD 50% Bonus Money up to ₹20K. Deposit code ‘ALLIN50’ Register -

Junglee Poker

Sign-up and get bonus

Offer: Up to ₹50,000* Register -

Calling Station

Sign-up with promo code 'AFFCSGUT'

Offer: 30% FTD bonus with code FTD30 Register -

WinZo Poker

Daily Winnings Up To ₹40 Crore!

Offer: Get ₹550 Joining Bonus For Free Register -

Stake Poker

Welcome bonus

Offer: 200% up to ₹120,000 Register

Newsletter

Thank you for subscribing to our newsletter.

This will close in 20 seconds